Three months after Aisha starting working in a prison, she was talking to a group of prisoners in the kitchen when one of them said to her, ‘I can always tell when you are on duty…’

Curious about this statement, Aisha wondered how this guy knew her shift patterns, but she smiled as she asked how he knew when she was on duty.

He answered, ‘because there is always a stink of fish when you are here!’

She felt like she had been punched in the face. She was dazed by the pure nastiness of the comment and felt a burning sense of humiliation as everyone, including her colleagues, laughed out loud in response to the jibe.

She told me that she pretended to laugh and waited for about 30 seconds (which felt like an eternity) before nonchalantly making her way to the changing room and spraying herself with every possible spray she had. Jokingly, she even thought about using air freshener on herself.

Ian was working in a call centre for a utility company in Scotland when an irate customer on the line barked that he had been waiting for hours to get through and demanded to know how £23 had been taken out of his account without his say so.

Ian remained calm and listened to the customer rant about this ‘violation’ and ‘breach of trust’. Ian tried to reassure him that he would endeavour to get to the bottom of the complaint and call the customer back, but that wasn’t enough apparently.

The furious customer was now shouting and swearing, and just as Ian was about to remind the customer that he did not need to listen to such language, the abuser then shouted, ‘ I f*****g know you. You f*****g paedophile. I know what you do.’

Ian was stunned and horrified by that statement, immediately terminated the call, and looked anxiously to his colleagues. He could not forget this incident and the prospect of answering future calls began to cause him anxiety.

These two scenarios are extreme examples of verbal abuse. Thankfully, situations like these are rare.

Though these are extreme examples, each had a dramatic impact on the target’s psychological well-being.

The abuse in each was designed to be hurtful and cause distress to the target. They were incidents that left each target feeling vulnerable and wanting reassurance of support from supervisors and colleagues. The targets also wanted to know how they could respond to situations like these in the future.

Although Aisha’s incident was face to face and Ian’s was thankfully over the telephone, they shared one critical fact: neither of them received any kind of support, guidance, or training to help them cope better in the future. In fact, each were told in their own way that such situations are part of the job!

What the Law Says About Verbal Abuse

There are three main pieces of legislation that matter when it comes to verbal abuse:

The Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 (HSW Act) – Employers have a legal duty under this Act to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of their employees. They must provide whatever instruction, information and training to do so.

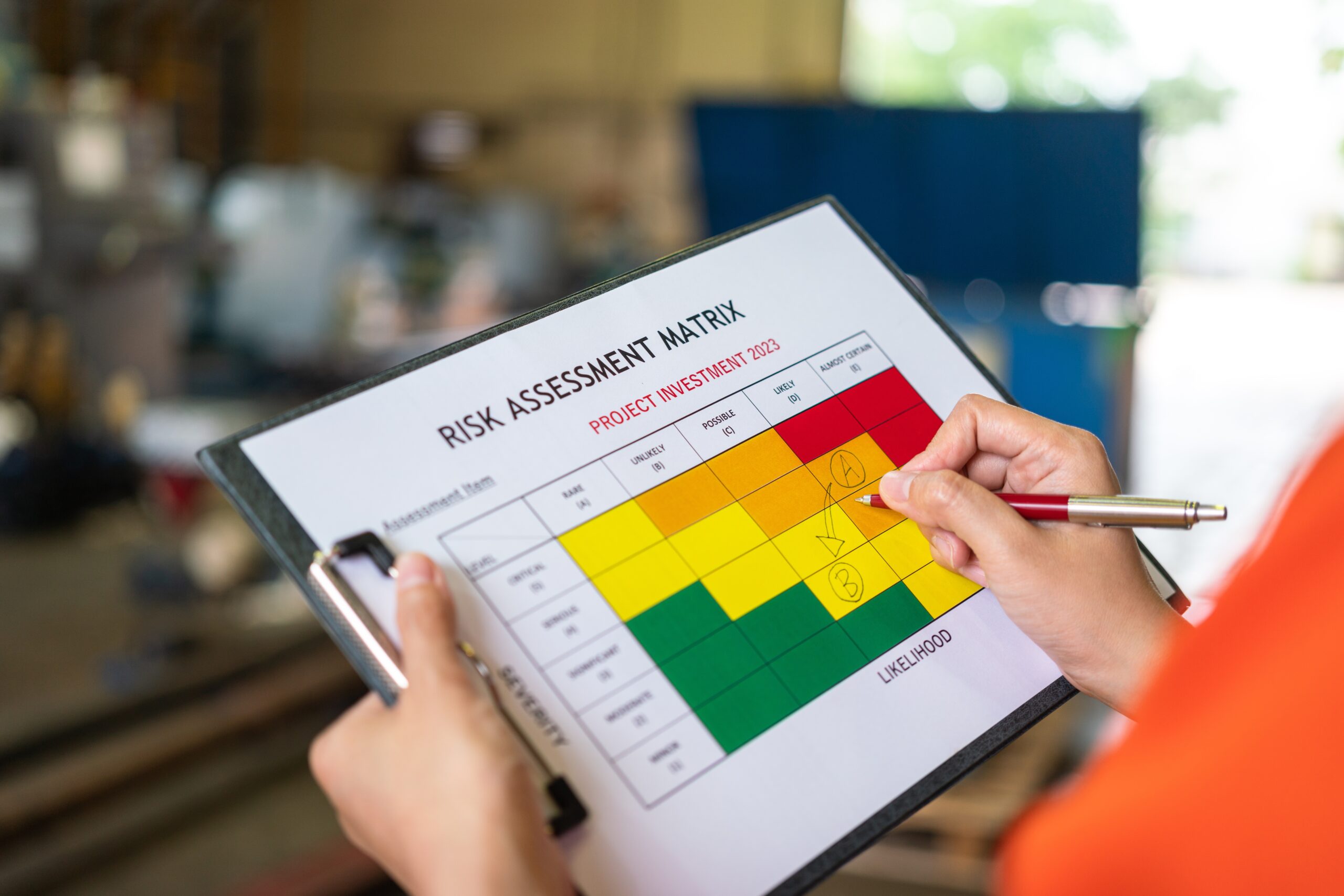

The Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999 – Employers must assess the risks to employees and make arrangements for their health and safety by effective:

- Planning

- Organisation

- Control

- Monitoring and review

The risks covered should, where appropriate, include the need to protect employees from exposure to reasonably foreseeable violence.

Safety Representatives and Safety Committees Regulations 1977 and The Health and Safety (Consultation with Employees) Regulations 1996 – these laws state that employers must inform, and consult with, employees in good time on matters relating to their health and safety.

Reporting of Injuries, Diseases and Dangerous Occurrences Regulations 2013 (RIDDOR) – This legislation requires employers to report and keep records of any work-related accidents and incidents that may endanger health and safety.

Unfortunately, RIDDOR only make reference to any act of non-consensual violence done to a person at work. So, it clearly states this is about physical violence only.

Verbal Abuse is Abuse

Psychological injury and/or emotional distress are not usually classified as injuries resulting from verbal abuse.

But, if you check the HSE’s definition of workplace violence, you will find it states it is…

‘Any incident in which a person is abused, threatened or assaulted in circumstances relating to their work.’

Threats and verbal abuse are part of the definition, yet are still poorly dealt with in the workplace.

There is clear evidence that exposure to verbal abuse can result in the target becoming, anxious, angry, distressed, and in some instances, psychologically traumatised.

A further disheartening fact is that the more people that are exposed to verbal abuse the greater the likelihood of accepting such behaviour and normalising it!

This creates a perverse situation in which a target of verbal abuse can be made to feel that they are the problem for not merely accepting the abuse as part of the job.

When a target reports an instance of abuse to supervisors or managers, the target can be made to feel like a trouble maker or someone not suitable for the position. Such responses often discourage the target, who will then stop recording such incidents and try to accept them as ‘part of their development.’ This is wrong and unacceptable in any modern work environment.

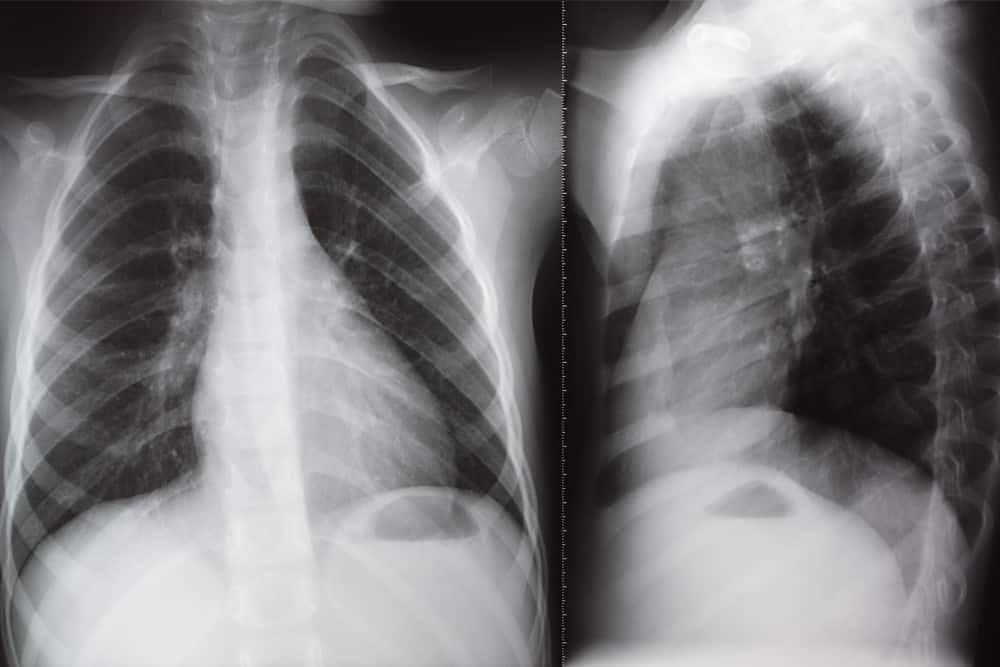

Verbal Abuse Facts & Figures

The Health and Safety Executive’s (HSE’s) Violence at Work Statistics for 2019/20 (published in November 2020 recorded 688,000 incidents of violence at work involving adults of working age.

Of these 688,000 incidents, 389,000 involved threats of violence and undoubtedly included verbal abuse. Some 62% of the incidents involved no injuries sustained.

Woefully Unprepared

Twenty years ago, I reported in Personnel Today that despite verbal abuse and/or threats of violence nearly outnumbering physically violent incidents by five to one, the number of training courses that specialised in dealing with verbal abuse were virtually non-existent.

Too often employers think that good de-escalatory skills will calm a person and therefore reduce the likelihood of someone being verbally abused. This can work when the verbal abuse is caused by anger and a sense of injustice. However, the best defusing skills in the world prove useless when (as in Aisha’s case) what is said is done deliberately to hurt and humiliate the target.

As long ago as 1992, psychologist Dr Wiliam Dubin *[1] differentiated between what he called ‘hot’ and ‘cold’ threats. By ‘hot’ verbal abuse, he was referring to verbal abuse that is linked to a person feeling angry, when they feel they are the victim of an injustice. Often this kind of verbal abuse is receptive to de-escalatory (calming) response. As they calm down the accompanying verbal abuse will diminish also. We often associate anger with heat.

Cold verbal abuse is perfectly illustrated in the opening scenario. The abuser wasn’t upset or acutely angry. He was calm, relaxed and deliberate with what he said. His aim was to use his hurtful comments to cause pain, distress or anger. This is the kind of verbal abuse many targets will find more difficult to deal with.

* [1] Dubin W ( 1995) Maier GJ, & Miller RD: Management & Treatment of the violent patient. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association Florida.

Learning to Cope with Verbal Abuse

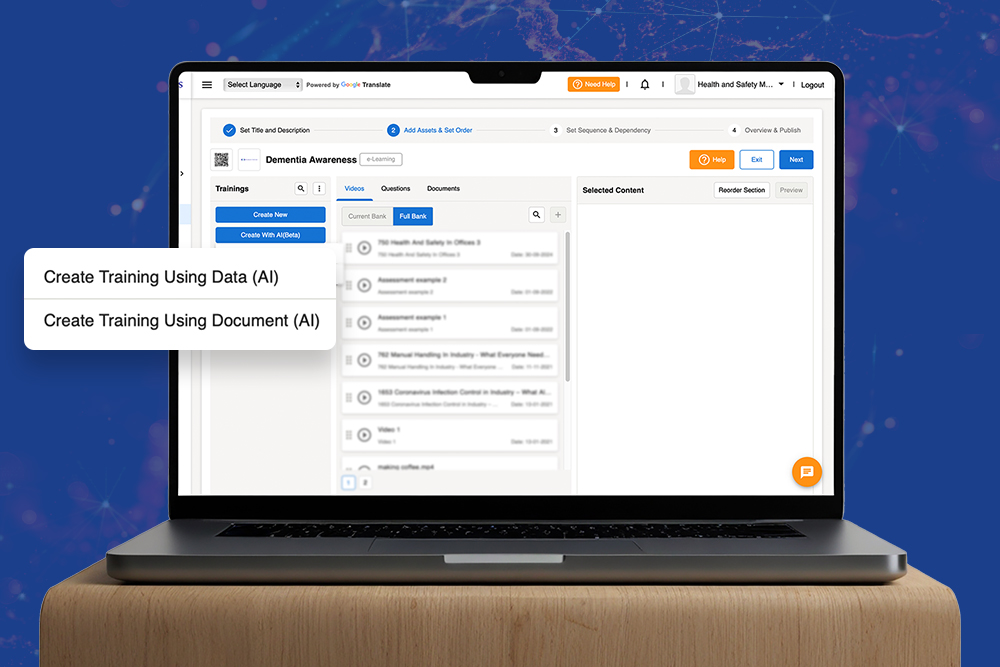

In 1998, I devised a training course called, ‘Sticks and Stones’. It was designed in response to Aisha’s story and attempted to show how to cope with and manage verbal abuse. But it specifically looked at how to handle those who do not respond to a defusing or calming approach.

As part of the Sticks and Stones programme I developed a script or verbal abuse index to assess how participants responded to different comments and how they perceived the statements compared to colleagues.

Each of the statements are read out and then, using role play, delivered face to face to demonstrate how interpretation of a spoken statement can be significantly different from the same statement when read.

The participants are asked to score the statements from 1-5 in terms of how they interpret them in writing and again when they are uttered at them directly from the course leader or a colleague.

The Verbal Abuse Index

Score each of the following on a scale of 1 to 5

1= No impact at all – it is negligible

2= Irritating but not a problem for me

3= Irritating and not comfortable

4= Offensive and not acceptable

5= Deeply offensive and distressing

The idea of this index, is that it allows employers to gain an understanding of the fact that verbal abuse can be subjective and what one person finds difficult, a more experienced colleague may view as water off a duck’s back. It can also allow employees to identify the type of verbal abuse they may struggle with and seek guidance on how to best deal with the abuse.

It also enables employers to identify the serious nature of verbal abuse and help employees to develop professional, but effective responses and finally it enables employers to gather data on verbal abuse and design training to address verbal abuse.

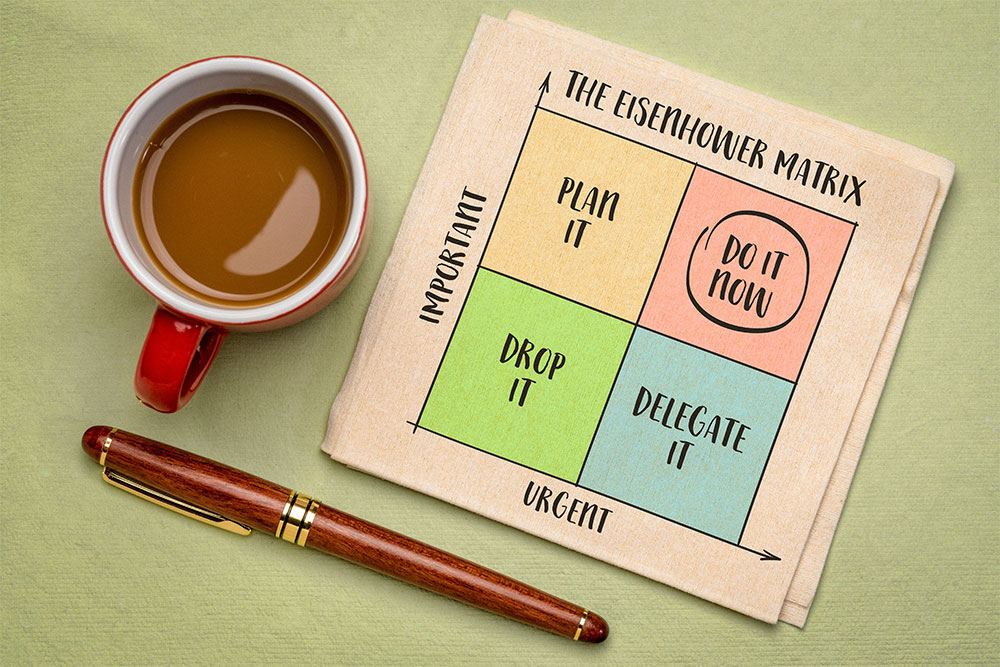

What can you do?

Do you just ignore verbal abuse aimed at you, or do you respond with a crafty put down? Do you laugh, apologise, shout back or burst into tears?

Knowing ourselves is a crucial part of managing stressful situations. The fact is, some days we can ignore verbal abuse totally, and other days it can get under our skin and wind us up.

One useful tool is self-talk. Self-talk is a concept developed by psychologist to help people overcome negative thoughts and feelings. It’s almost as if you are coaching yourself, saying, ‘you can manage this situation, take nice deep breaths, you can think about something totally unrelated to this. Imagine a lovely hot bath or being with your loved one on holiday. You are great at your job, remember this.’

Linked to self talk is the ability to put things in perspective. Imagine how you may be feeling when you’re targeted for verbal abuse. Score your feelings of discomfort or distress out of 100. Now imagine something bad happening to someone you love.

Suddenly, instead of scoring the verbal abuse at 85 or 90, your loved ones and something happening to them relegates the verbal abuse to a a position way down the score ladder, emphasizing its unimportance.

Always try to have a script that empowers you: ‘Mr Jones I’m sorry you are feeling angry and upset. However, I’m here to help you. I’m not here to be verbally abused or swore at. If you do not or cannot moderate your language, I will terminate the call or I will walk away from this situation and report the incident as one of verbal abuse.’

Or, ‘Please don’t speak to me like that. Verbal abuse is not acceptable. I will not accept it and I will report it.’

Being able to walk away is only possible if it is safe to do so.

One technique that many sports people use to concentrate on either kicking a penalty or hitting a golf shot, is development of a mantra, a word or a saying that you keep repeating to yourself over and over again. This enables you to concentrate on the mantra and help shut out shouting and screaming from outside. This can be really useful for dealing with verbal abuse. The mantra may be something profound or even something as simple as a favourite meal – ‘Cheese on toast’.

Remember that you are entitled to receive training and protection measures to keep you safe and able to do your work.

Despite what you may be told sometimes, the customer is always right…unless they’re wrong.

No one is employed as a punching bag and no one is employed to be verbally assaulted.