Imagine you’ve asked someone to do something for you at work.

You thought carefully about your words, gave clear instructions and included a deadline. The listener nodded along, confirmed they understood and got straight to work.

But now it’s a day later and you’ve realised your colleague has completely missed the point.

If you’ve ever been in this situation, you’ve probably been left wondering what went wrong. The Shannon and Weaver model of communication might give you the answer.

Our guide explores this famous communication theory, its history and how you can use it to improve your interactions at work and ensure your requests are understood.

The History of the Model

American mathematicians Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver originally conceived the model in 1948. It was published in their paper ‘A Mathematical Theory of Communication’ before being expanded upon in a book published a year later.

The model was developed to represent the basic elements of communication and explain how messages can become lost or distorted. Shannon and Weaver believed that by identifying barriers to communication, you could develop strategies to overcome them.

Since its inception, Shannon and Weaver’s theory has been widely embraced and is considered one of the most influential models of communication of the 20th century.

The Model Explained

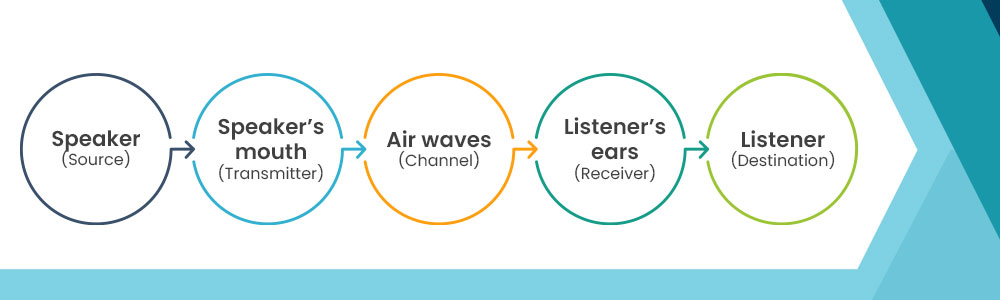

The model breaks effective communication down into five elements:

Source – the person who decides on and creates the message

Transmitter – the element that translates the message into a signal

Channel – the way the signal is delivered/carried

Receiver – the part that translates the signal back into a message

Destination – the person the message was intended for

Example of Shannon-Weaver Model of Communication

Thinking of communication this way can seem overly complicated. So, let’s look at the most basic form of communication—speaking to someone face-to-face—as an example of the Shannon-Weaver model of communication.

The Impact of Noise

In addition to these five elements, Shannon and Weaver also considered the impact of ‘noise’ on effective communication.

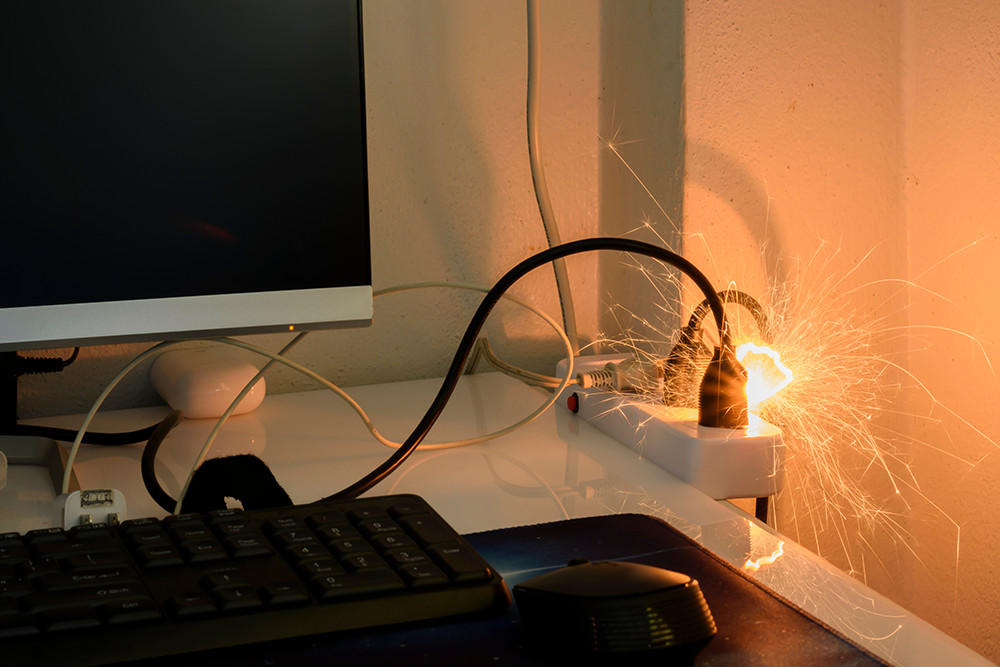

Noise is classified as anything that might distort the message. In our example of face-to-face communication, noise might be an external sound, such as a fire alarm. The interruption from a loud alarm would make it difficult for the receiver to understand what the source is saying.

Alternatively, noise might be considered internal. The following day, the two people might try and have another conversation. But the person speaking – the source – might be a little tired and mumbling while speaking. The unclear words would also make it difficult for the receiver to understand the message.

There are other forms of internal noise. When applying the model to other forms of communication, noise might be a technical issue that disrupts the channel. For example, in a telephone call, the ‘noise’ might be a problem with the phone line. For a Zoom call, the ‘noise’ might be dropping the Wi-Fi signal.

Advantages of Applying the Model at Work

You can use the model to identify and overcome issues affecting your communication ability in various mediums.

Helps Overcome Communication Barriers

The original model identified three levels where communication can be interrupted:

- Technical – issues that affect the accuracy of the message being sent

- Semantic – problems that affect the meaning of the message

- Effectiveness – this issue arises when the receiver doesn’t respond in the way the source wanted

Again, it helps to illustrate these issues with examples:

Technical problems can be obvious and are usually the most straightforward to fix. They might be a faulty phone, poor Wi-Fi signal or loud music drowning out a conversation.

Semantic issues are a little more complex. The two people communicating might have a different understanding of the words used. For example, it’s a Monday, and someone requested a meeting next Thursday without specifying the date. Would they mean the Thursday in two days or the following week? Both interpretations are valid, which means the meaning isn’t clear because of a semantic problem.

Effectiveness issues are also nuanced. Shannon and Weaver assume that every person has an ideal outcome in mind when communicating with another person. But this perfect outcome isn’t always achieved. Imagine your manager asks you to make a specific report your priority. They might want you to drop everything else and work exclusively on it.

But you might interpret the message as ‘this report is important’ and finish working on another task first. In this example, the message failed because the manager (the source) didn’t get the outcome they wanted.

Applies to Different Forms of Communication

The roots of the Shannon and Weaver model are in telecommunications. It was initially intended to understand technical communication. However, the model can be applied to almost any form of communication, even if some applications might double up on certain elements.

For example, there are two transmitters in a phone conversation: the person’s mouth and the phone itself. But the principles of the model are still relevant. They can help you identify issues preventing you from conveying a message clearly.

Disadvantages of Applying the Model at Work

Although the model was initially acclaimed, other theorists have pointed out several shortcomings in the intervening years.

Doesn’t Consider Feedback

The original model doesn’t consider feedback. It assumes that the source delivers a message the receiver understands or does not understand.

In real exchanges, we would likely ask someone to repeat themselves or explain something if we don’t understand.

Ignores Power Dynamics

There are clear hierarchies in play at work. And someone’s authority affects the way they communicate and how they’re understood.

A junior employee making demands won’t get the same response as the managing director. The model would label this an effectiveness issue, but we would recognise this as the junior employee acting up. Even the most skilled communicators need to consider power dynamics in the workplace.

Only Applies to One-on-One Communication

Shannon and Weaver designed the model for one-on-one communications. But, meetings and group discussions are regular occurrences in the modern workplace.

For example, presentations are an example of one-to-many communication. The model wouldn’t be workable in this type of situation.

Where to Learn New Communication Skills

The Shannon and Weaver model of communication can help you overcome communication barriers at work. But who thinks applying a 70-year-old mathematical communication theory to every email or catch-up with a co-worker is the best way to make yourself understood? Luckily, there are much easier ways to overcome barriers to effective communication.

Our online Communication Skills Training will make you a better communicator at work. You’ll learn to communicate effectively, including using body language and facial expressions. Plus, you’ll master active listening and recognise the importance of empathy in building productive relationships at work. Becoming a better communicator will boost your confidence, promote collaboration and ensure your messages are understood even when the fire alarm’s going off.