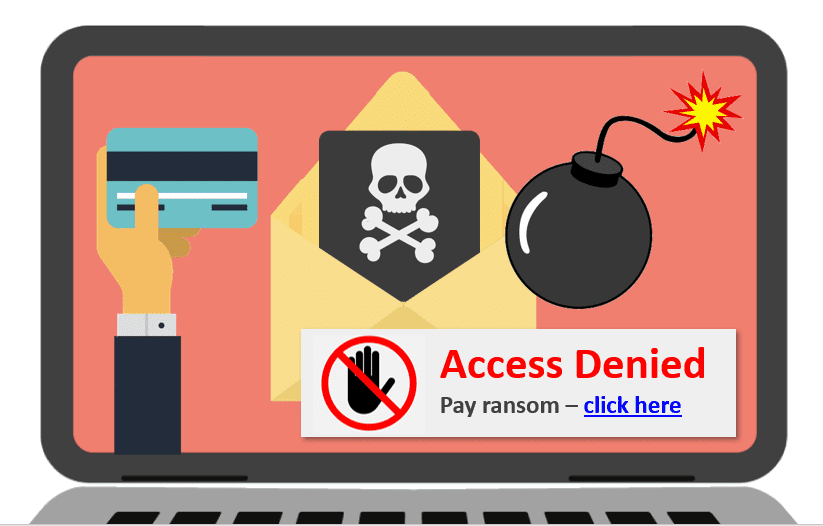

Money laundering is a major problem in the UK. Criminals launder billions of pounds here every year, exploiting the UK’s businesses and financial services sector to disguise illicit cash as legitimate funds, ready to be reinvested in drugs, human trafficking, or terrorist acts.

To stop this cycle, professionals who handle large transactions or work in finance have a legal duty to detect and prevent money laundering. Any reasonable suspicions have to be reported swiftly before criminal proceeds slip into the legitimate economy. Failing to report is a criminal offence.

This guide explains how to report money laundering. It also covers the key warning signs, when reports are required, and who they need to be shared with.

Key Takeaways

- Money laundering must be reported under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002. Failure to report is a criminal offence.

- Suspicious activity should be reported to your organisation’s money laundering reporting officer (MLRO) unless doing so could alert the suspect or your organisation has no MLRO.

- If you do not have an MLRO in your organisation (or they’re compromised), you must submit a suspicious activity report directly to the National Crime Agency (NCA).

- Suspicious activity reports are submitted through the NCA’s online reporting portal.

What Money Laundering Is

Money laundering is the process of disguising criminal proceeds as legitimate funds. Criminals introduce “dirty” money into the economy before moving it through multiple transactions to “clean” it and obscure its origin. Eventually, the laundered money can be spent or reinvested without raising suspicion.

The process typically follows three stages:

- Placement – Dirty money is introduced into the financial system, often through cash-intensive businesses or high-value asset purchases.

- Layering – The money is moved through multiple transactions, bank accounts, or international transfers to hide its origin.

- Integration – Once laundered, the money appears clean and can be used without detection, often reinvested in businesses or property.

Money laundering is easiest to detect at the placement stage, which is why anti-money laundering legislation focuses on detection and prevention.

The Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing and Transfer of Funds Regulations 2017 (MLR 2017) sets out strict anti-money laundering (AML) requirements for banks as well as businesses that handle large transactions vulnerable to criminal exploitation.

Businesses under MLR 2017 have to adopt a risk-based approach to money laundering prevention. Each transaction and customer must be examined and assessed for money laundering risks. Higher-risk activities need to be scrutinised and may need to be reported (more on this later).

In addition to MLR 2017, businesses must also comply with the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (POCA).

POCA makes it illegal to conceal, disguise, convert, or transfer criminal property. Crucially, it also makes failing to report a criminal act. If you don’t report suspicions or you alert the customer you’re suspicious of (known as tipping off), you can be prosecuted under POCA.

Who Has a Duty to Report Money Laundering

POCA applies to everyone. Any person or business – regardless of sector – can be prosecuted for failing to report suspicious financial activity.

What Happens if You Don’t Make a Report

Failing to report money laundering is a criminal offence under POCA. If you have reasonable grounds to suspect money laundering but fail to act, you could face:

- Unlimited fines – The regulator for your industry can impose severe financial penalties on you or your organisation if you fail to report.

- Prison sentences – Failing to report can lead to up to five years in prison. Tipping off a suspect about a report carries the same penalty.

- Disqualification – You risk losing your licence or being banned from holding certain positions if you work in a regulated sector.

Signs of Money Laundering

Spotting money laundering isn’t always straightforward. But certain high-risk transactions and customer behaviours should raise suspicion, especially if they’re out of character or unusual for your business.

High-Risk Transactions

- Large cash payments – Especially if cash payments are rare for your business or industry.

- Rapid movement of funds – Money that’s quickly transferred between multiple accounts with no clear business purpose is grounds for suspicion.

- International transfers to high-risk jurisdictions – Payments sent to or received from countries known for weak financial regulations.

- Overpayments or refunds – Customers deliberately overpaying and requesting a refund to a different account.

- Unusual asset purchases – Buying high-value goods (property, luxury cars, jewellery) with no clear source of income.

- Sudden or drastic changes in transaction patterns – Large increases or decreases in transaction amounts or frequency with no clear explanation.

High-Risk Customer Behaviours

- Reluctance to provide information – Customers avoiding questions about their identity, business activity, or source of funds.

- Politically exposed persons (PEPs) – Individuals with high-level political or public roles who may be vulnerable to corruption.

- Use of intermediaries – Transactions conducted through third parties with no logical business connection.

- Frequent account changes – Sudden or repeated changes to bank accounts, beneficiaries, or payment structures.

- Mismatch between income and transactions – Customers whose spending or deposits far exceed their declared income.

Not every unusual transaction is evidence of money laundering, but you shouldn’t ignore any of these red flags. If you have reasonable suspicions, you need to report them to the relevant authority.

How to Report Money Laundering

Money laundering suspicions should be reported internally first. In most regulated businesses, concerns should be escalated to the money laundering reporting officer (MLRO), who will assess the risk and decide whether to file a report with the National Crime Agency (NCA).

If there is no MLRO in your organisation, or if you believe reporting internally could compromise an investigation, you must submit a suspicious activity report (SAR) directly to the NCA.

Reports are legally required when there are reasonable grounds to suspect money laundering, even if the transaction has not yet been completed.

How to Report Money Laundering Inside Your Organisation

If you suspect money laundering, you must report it to your MLRO as soon as possible, following your organisation’s internal procedures.

A typical reporting process includes:

- Documenting concerns – Record key details, including the parties involved, transaction amounts, and why you suspect money laundering.

- Submitting an internal report – Provide this information to the MLRO through your organisation’s reporting system or designated process.

- MLRO review – The MLRO assesses the report, gathers additional information if needed, and decides whether to escalate the case.

- Decision to report externally – If the suspicion is credible, the MLRO submits a suspicious activity report to the National Crime Agency.

Remember, you cannot inform the customer that a report has been made. Alerting the party under suspicion could be considered tipping off, which is a criminal offence under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002.

How to Report Money Laundering Outside Your Organisation

If your organisation doesn’t have an MLRO, or if you believe internal reporting could compromise an investigation, you must submit a suspicious activity report directly to the National Crime Agency.

Suspicious activity reports should be made when you have reasonable grounds to suspect money laundering – even if a transaction has not yet been completed. Reports must be detailed and factual, including:

- The individuals or entities involved

- The nature of the suspicious activity

- Relevant dates, transaction amounts, and account details

- Any supporting evidence or documents

(SARs are submitted online through the NCA’s reporting portal.)

Again, you must not inform the person under suspicion, as doing so could constitute tipping off.

Defence Against Money Laundering

If a transaction is suspected to involve criminal property but must proceed, a SAR should include a specific request for a defence against money laundering (DAML).

A DAML is necessary when delaying or refusing the transaction is not possible, such as when a business is legally obligated to complete a contract or risks breaching financial regulations by holding client funds.

If granted, a DAML provides legal protection against prosecution for proceeding with the transaction.

Anti-Money Laundering Training

Before you can report money laundering, you need to recognise when it’s happening. Knowing what counts as high-risk activity, understanding what makes a transaction suspicious, and being confident in when and how to report are all essential to staying compliant.

Our online Anti-Money Laundering (AML) Training course will help you understand your AML duties and protect your business from criminal exploitation. It covers:

- High-risk transactions and behaviours

- Necessary controls, including customer due diligence

- Employee’s responsibilities to identify and report money laundering

Certified by CPD, this course will help you and your team recognise money laundering red flags and meet your reporting duties.