We all have the right to live our lives in the way that we choose. However, some people suffer from mental health conditions that can prevent them from making important decisions for themselves.

When such situations arise, there are many important considerations. For instance, how do we determine if someone has a lack of mental capacity and should have decisions made on their behalf? And how do we ensure decisions are made with that individual’s best interest in mind? Fortunately, legislation exists to help us answer these questions.

In this blog, we explore the five principles of the Mental Capacity Act and how they inform decision-making on behalf of individuals who can’t advocate for themselves.

Key Takeaways:

- The Mental Capacity Act 2005 provides a legal framework to protect and empower people who may lack the capacity to make some or all of their own decisions about care and treatment.

- The five principles of the Mental Capacity Act are values that underpin the legal requirements of the act.

- Principles 1 to 3 support in determining if a person lacks mental capacity to make a decision, while principles 4 and 5 guide in making a decision for them.

- The five principles of the Mental Capacity Act must be applied when advocating for someone who may lack mental capacity to make their own decisions.

What Is the Mental Capacity Act?

When a person cannot make decisions concerning their own health and wellbeing, the principles of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 are used to help others make decisions on their behalf.

The Act came into force in England and Wales in 2007. The five principles of the Mental Capacity Act must now be applied when advocating for an individual who lacks the ability to make decisions for themselves.

Whoever is applying the principles of the Act must have a full understanding of each principle and how it applies to an individual’s circumstances.

What Does ‘Lack Mental Capacity’ Mean?

According to the Mental Capacity Act 2005, “a person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain.”

Lacking mental capacity can be either permanent or short-term. Permanent lack of mental capacity is where the ability to make decisions for yourself is always affected. This may be due to conditions like dementia, suffering a brain injury or having a severe learning disability.

A short-term lack of mental capacity is where the ability to make decisions changes, from day to day. Some mental health conditions can cause this, such as schizophrenia. Medications or when someone is unconscious can also mean that they have a lack of mental capacity.

How Do You Know If Someone Has Lost Their Mental Capacity?

The Mental Capacity Act has a two-stage test to determine if a person is unable to make decisions independently:

- Does the person you’re in charge of providing care have an impaired or disturbed mental function?

- Does the impairment of disturbance make them unable to make a specific decision when needed?

If the answer to both these questions is yes, then the person lacks the mental capacity to make that specific decision and may require assistance in making it.

Who Can Determine a Lack of Mental Capacity?

Determining a lack of mental capacity usually falls to family members who are close to the person in question. But, it also involves those who help care for the person regularly. If you need help making this decision, you can ask for the assistance of a doctor or another medical professional.

Mental Health Courses

Our mental wellness courses help overcome the stigma associated with mental health challenges and provide practical techniques for managing such challenges in professional settings. The courses aim to protect employees’ mental well-being, improve productivity and enhance work and personal life balance.

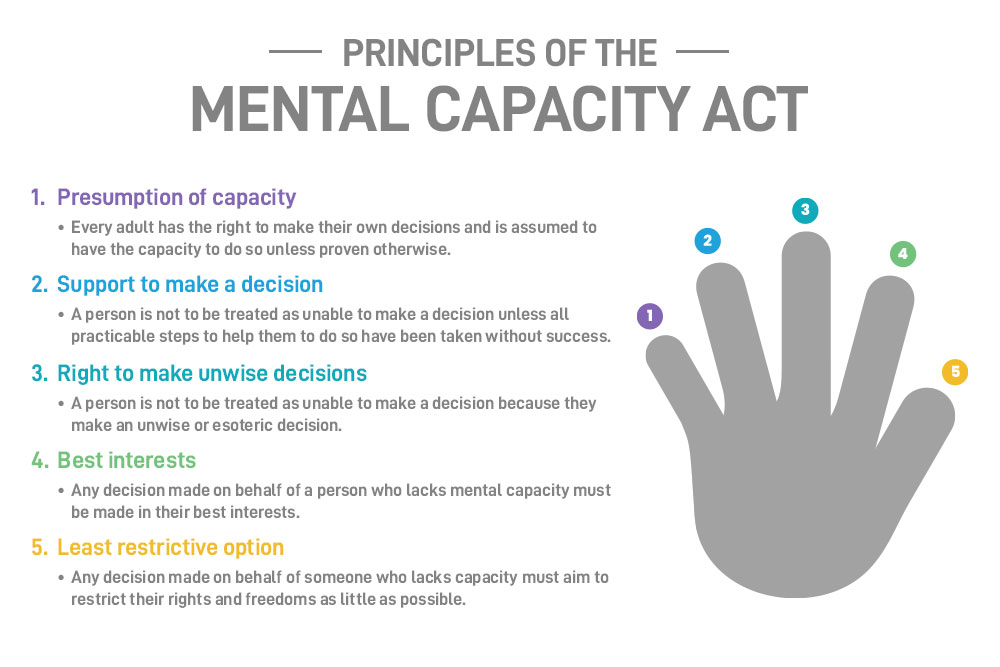

5 Principles of The Mental Capacity Act

The Mental Capacity Act is comprised of five key principles. They’re designed to protect the rights and freedoms of individuals who may lack the capacity to make certain decisions. The five principles are:

- Presumption of capacity

- Support to make a decision

- Right to make unwise decisions

- Best interests

- Least restrictive option

Principles 4 and 5 are only applied when an assessment finds the assessed individual does not have the mental capacity for the decision in question.

Let’s look at each of the five principles to get a better understanding. It is important to remember that cases are based on individual circumstances, as we are all unique.

Principle 1 - Presumption of Capacity

— Mental Capacity Act 2005, Section 1(2)

As adults, we all have the right to make our own decisions. It simply can’t be presumed that we can’t make decisions on the basis of our age, behaviour, condition or appearance. It will have to be proven.

For example, it can’t be assumed that someone who has suffered a stroke that impaired their ability to communicate is not capable of making decisions for themselves due to their difficulty expressing themselves. Similarly, lacking the capacity to manage finances doesn’t mean someone is unable to decide on the medical treatment they need to receive.

If a person lacked the capacity to make a previous decision, they may still be capable of making the next one.

Principle 2 - Support to Make a Decision

— Mental Capacity Act 2005, Section 1(3)

Before you can decide that someone lacks capacity, you must take all practicable steps to help them make the decision themselves.

This includes doing everything reasonable to ensure they understand the decision, what it involves, and how to communicate their choice.

Practical ways to provide support include:

- Discussing the decision at a time when they are more alert and coherent

- Using a communication style that suits them

- Explaining all relevant information clearly and allowing time to process it

Principle 3 – Right to Make Unwise Decisions

— Mental Capacity Act 2005, Section 1(4)

We all make unwise decisions; we’re human after all. This principle states that a person cannot be treated as though they are unable to make decisions for themselves simply because they may make a decision that seems ill-advised or difficult to understand. In such cases, the aim is to examine how they make decisions rather than the decisions themselves.

Assessing only the decision made essentially means that the assessor is applying their own societal values and beliefs to the decision, and not those of the person being assessed.

Principle 4 - Best Interests

— Mental Capacity Act 2005, Section 1(5)

All decisions made on behalf of a person who lacks the mental capacity to do so themselves must be in their best interest. ‘Best interest’ does not have a legal definition, and as every person and circumstance is different, this may seem like a grey area.

Section 4 of the Mental Capacity Act sets out a procedure to follow to help in deciding what is in the best interest on behalf of a person who lacks mental capacity.

Principle 5 - Least Restrictive of Rights and Freedom

— Mental Capacity Act 2005, Section 1(6)

This principle states that when a decision is made on behalf of someone who lacks mental capacity, the least restrictive option available should be taken. This is to ensure their rights and freedoms are not infringed upon.

It means that the person in a position to make the decision will need to consider a number of less restrictive options before the final decision is made. This is both fair and just, and how we would all want to be treated.

Gain the Necessary Depth of Safeguarding Knowledge

If you or your team come into contact with children or vulnerable adults, you have a responsibility and a role to help keep them safe.

Human Focus provides a range of safeguarding courses to equip individuals with the knowledge and skills needed to recognise, prevent, and respond effectively to instances of abuse, neglect or exploitation against children and vulnerable adults in their field.